On the last day of my break, I had a dream.

I was in one of the ship’s viewing ports again, alone. But Grandma’s wheelchair was there with me. Like last time, I couldn’t just see out of one wall; I could see all around. The Vanguard to ship-right, which was ‘behind’ from the outside of the ship, the direction we were travelling away from. The Dragonseye to ship-left, bright and hot, ‘ahead’ of us. I don’t normally think much about what direction things are from outside the ship, how left is forward and right is backward and ship-forward is anticlockwise (if you’re looking at the ship from ‘behind’) and backward is clockwise. It doesn’t matter, really, not from the inside. But here, being able to see in all four directions, I could understand both ways of seeing the directions at the same time.

The floor beneath me was solid. The roof above me was not. And, like last time, I knew that ‘up’ was transparent too, but there was something so big, so foreboding, something that it would change everything just to look at, up there, something whose pressure I could feel without looking at it the same as I could see the light of the Dragonseye reflecting off everything without looking at the star.

But I wasn’t afraid, this time.

I hadn’t understood, last time I’d had this dream. But I understood now. I was someone different, now. I was someone who had seen the sheep.

I could feel its grease on my fingers, its meat on my tongue. And I looked up.

I didn’t really have a way to envision the treegrave. I’d been on a trip to the treegrave before, but all we’d really seen was the big aspen forest near the elevator, and our tour guide had talked about the symbolism of the aspen tree and how it makes a forest and how we, the successors of Aspen Greaves and the First Crew, were building our own interstellar forest of humanity. But that wasn’t really the treegrave. The treegrave was all those minds hooked up to a big computer, the brain of the ship, that controlled and maintained everything and saw everything and everyone. And I didn’t really know what that looked like. In my dream, it was just a light, a big, soft light that I was slowly orbiting, way more important than the silly light of the star we were moving around which was just real light, and boring.

The Courageous isn’t a closed system, but it’s as close as we can make it. It has to be, to last so long in space between stars. Wool becomes fabric becomes clothes, until they’re too worn out to be worn or repaired any more, becomes rags or cushioning or insulation, becomes broken down in the biotanks and becomes a hundred other things including, maybe someday, more wool. Aluminium becomes a fork that is used until it’s bent out of shape, then it becomes a piece of someone’s art project, then when they die or clean out their things it gets melted down and turned into other aluminium things. Birthday charms are thrown into recycling and washed and put in new birthday eggs and thrown into recycling, until they’re scratched or dented, and get recast. Food and air and metals and rubber and water, all cycled around.

And people, too. That’s the secret of the sheep.

Because that sheep, that animal, walking around and bleating and letting me touch it and then walking away, was a first order organic factory. As much as the biotanks or the bone pits or the wool wall. The proof of that was the taste of its meat in my mouth, that I could taste again in the dream. It was alive, the same as all first order organics factories, the same as the biotanks and the skin on the wool wall and the bone cells in the bone pits and the rice in the rice gardens.

And the same as the plants in front of me in the dream, in their little garden bed in the viewport. They didn’t make food, but they made oxygen. When they died, they would be compost.

The same as us.

We think of people as being different, because we’re the most important part of the ship. And we are the most important; you can’t fill the universe with people if you don’t have, well, people. Everything else was there to support us, to keep us alive and safe and happy and able to keep being people. We were the most important part.

But we were still a part.

I looked up at the treegrave, at the ship’s brain, something made of recyclable inorganics (metals) and first order organics produced by human organics factories (human brains) and I felt so, so small. My dad had once told me about how real blood, the blood in us not the blood in the wool wall, was full of cells all rushing about our body to carry air and food and stuff around to our muscles and things. I felt like a little cell in the big body of the spaceship, on a jaunt learning to help keep it alive.

Do you see now, baby butterfly?

And then I woke up, breathing hard.

Not because of the dream. It was all pretty obvious, when I thought about it. I already knew that humans were made of meat and bones and things. Organics.

No. What I had remembered was that they’d said it would take ‘at least three months’ for Grandma to properly join the treegrave. And that had been five months ago. And I hadn’t heard anything from her.

So where was my grandma?

Something to ask the treegrave, maybe. I snuck out of my room, careful not to wake Ivy or Laisor. The lights in the common area were still on, which meant that one of my parents must be up. It must still be really early, but I didn’t want to go back to sleep.

I headed for the garden, for the red button to get the treegrave’s attention. And then I found out that, yeah, some of my parents were still up. Dad was sitting on the bench right next to the button, with Auntie Shorin sitting in his lap. Both half undressed, and kissing.

Really? Right next to the button? Hadn’t they heard of a bedroom, or a red house? Or somewhere else in the garden, even? I left before they could notice me. Talking to the treegrave was going to have to wait until morning. I could leave our home and go looking for a button somewhere else, but I wasn’t supposed to go walking around at sleeptime; if they noticed, I’d just scare everyone and get into trouble.

Besides, it would probably be a pain to find a button in public that was somewhere we could talk privately. It might be sleeptime for my family, but most of the ship was still up. Most of the ship is up at any time.

I went back to bed, but I didn’t go back to sleep. Five months was only two months longer than three months; maybe Grandma was just really slow at joining the treegrave. Nobody else was getting worried. But then, five months is also nearly two times three months. Should it take her twice as long to do something than it should?

We’d been told ‘at least three months’. They hadn’t given us a ‘less than’ time. I didn’t know how much time was normal. But it couldn’t be this long, right?

And maybe the rest of the family was worried. When the grown ups are worried about things, they sometimes try to hide it from me. They always think I’m too young to understand, and don’t want me to get upset. But she was my grandma! If something was wrong, I should know!

The more I thought about it, the more I thought that maybe I shouldn’t ask the treegrave. Because I was also thinking about the treegrave, and about how I didn’t know much about it. And about how when we’d gone on a tour up there, we had only seen the forest, and been told about the history of the place. And I’d never actually seen anyone who was hooked up to the treegrave. People went off to be part of the treegrave and nobody ever saw them again.

And it was horrible, but…

People were part of the ship. The most important part, but part of the ship. And people who were young and fit and healthy weren’t allowed to join the treegrave; only people only people who were old or sick or had something else about them that made a normal life hard, something that medicine couldn’t fix, were even allowed to apply. And then they get interviewed by counsellors and looked at by doctors and stuff, and they might still be told no if the doctors don’t think they should join.

That had always made sense to me, because of course they wanted to make sure that people who joined the treegrave were people who would be good at being part of the treegrave. The same as how you have to pass tests to be an engineer. But what if it was the opposite?

What if it was failing the health and psychology tests that let you become part of the treegrave?

I remembered the feeling of the sheep’s wool under my fingers, greasy and gritty and not as good as the wool wall, but still wool. The sheep’s job was to grow wool. It was a part of the ship. We were a part of the ship.

Grandma hadn’t worked for a few years before joining the treegrave. Her old bones hurt a lot, too. And she’d said that she was tired of being useless.

What do you do with a piece of the ship that doesn’t work properly? That’s too worn down to be helpful any more? You fix it. What do you do if you can’t fix it?

You recycle it.

Which joining the treegrave is, of course; Grandma’s brain worked fine, so why not use it if that’s what she wants? But what if it’s not that? What if there is no treegrave?

The only thing I’d ever seen (well, heard) of the treegrave was its voice. Robots could talk to people. They didn’t need human brains to talk to people.

What if the treegrave was a lie, to keep people’s loved ones happy after they took them away?

Had the Administration killed my grandma?

I was breathing very hard. I made myself take slow, deep breaths, like Auntie Moli had taught me. I didn’t need to be scared. Not yet. I could be wrong, just getting all tangled up over nothing. I didn’t have any proof.

Yet.

I would wait one more month, for Grandma to join the treegrave. I wouldn’t ask for her because then the treegrave would know and would fake her for me. But when she could, she would probably talk to me.

One more month. Two times the ‘at least three months’ we were told. That had to be enough time.

And if I hadn’t heard from her by then… then I would go looking for my grandma.

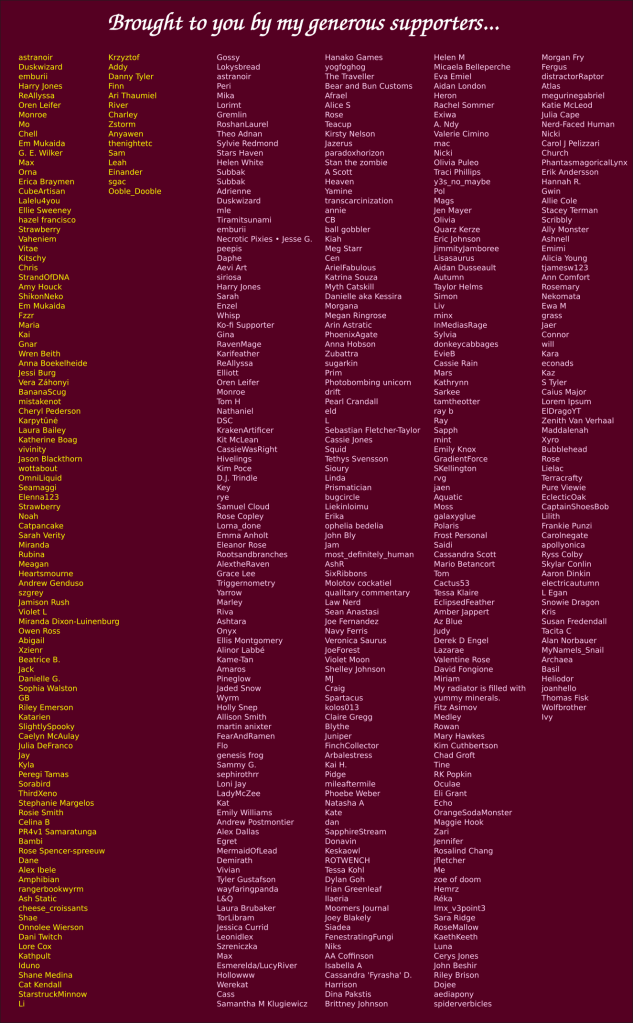

Those are some solid observations for a 7 year old. I wonder what she’ll learn? Thanks for the chapter.

LikeLike

oh, honey

as someone who’s read ttou, the treegrave is probably a real thing. But I still wonder if something happened with Taya’s grandma. Did her body reject the synthnerves or smth?

ig we’ll find out later ¯_(ツ)_/¯

LikeLike

I am worried about what Taya will do, and also the tree grave might not be able to do one person solidly, like the ai, I wonder if the people are sleeping the whole time, or awake like Aspen

LikeLike

Ah, I was wondering when something bad would happen

LikeLike